Neelum J Wadhwani Rational Review Irrational Results 84 Tex L Rev 801

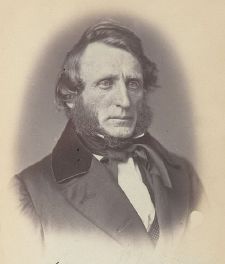

Congressman John Bingham of Ohio was the principal framer of the Equal Protection Clause.

The Equal Protection Clause, part of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, provides that "no state shall… deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws." The Equal Protection Clause can be seen equally an effort to secure the promise of the Usa' professed commitment to the proffer that "all men are created equal" past empowering the judiciary to enforce that principle against the states.

More concretely, the Equal Protection Clause, along with the residue of the Fourteenth Amendment, marked a groovy shift in American constitutionalism. Before the enactment of the Fourteenth Amendment, the Bill of Rights protected private rights only from invasion by the federal regime. After the Fourteenth Subpoena was enacted, the Constitution also protected rights from abridgment by state governments, even including some rights that arguably were non protected from abridgment by the federal government. In the wake of the Fourteenth Amendment, united states could non, amongst other things, deprive people of the equal protection of the laws. What exactly such a requirement means, of course, has been the subject of great debate; and the story of the Equal Protection Clause is the gradual explication of its meaning.

One of the main limitations in the Equal Protection Clause is that it limits only the powers of government bodies, and not the individual parties on whom it confers equal protection. This limitation has existed since 1883 and has not been overturned. Even so, since the 1960s, Congress has passed about civil rights legislation under its Commerce Clause ability.

Background

The words inscribed to a higher place the archway to the U.S. Supreme Courtroom are: "Equal justice under law"

The Fourteenth Amendment was enacted in 1868, shortly after the Union victory in the American Ceremonious War. Though the Thirteenth Amendment, which was proposed past Congress and ratified past united states in 1865, had abolished slavery, many ex-Confederate states adopted Black Codes following the war.

These laws severely restricted the power of blacks to hold belongings and form legally enforceable contracts. They likewise created harsher criminal penalties for blacks than for whites.[1] [2]

In response to the Black Codes, Congress enacted the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which provided that all those born in the U.s. were citizens of the Usa (this provision was meant to overturn the Supreme Court's decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford), and required that "citizens of every race and color ... [accept] full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of person and property, every bit is enjoyed past white citizens."[ii]

Doubts most whether Congress could legitimately enact such a law nether the then-existing Constitution led Congress to begin to draft and debate what would become the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The effort was led by the Radical Republicans of both houses of Congress, including John Bingham, Charles Sumner, and Thaddeus Stevens. The almost important among these, however, was Bingham, a Congressman from Ohio, who drafted the language of the Equal Protection Clause.

The Southern states were opposed to the Ceremonious Rights Human action, but in 1865 Congress, exercising its power under Article I, department 5, clause 1 of the Constitution, to "be the Judge of the … Qualifications of its ain Members," had excluded Southerners from Congress, declaring that their states, having seceded from the Union, could therefore not elect members to Congress. It was this fact—the fact that the Fourteenth Amendment was enacted past a "rump" Congress—that allowed the equal protection clause, which white Southerners almost uniformly hated, to be passed by Congress and proposed to u.s.. Its ratification past the former Confederate states was made a condition of their reacceptance into the Spousal relationship.[1] [3]

Past its terms, the clause restrains only country governments. However, the Fifth Amendment's due process guarantee, beginning with Bolling v. Sharpe (1954), has been interpreted as imposing the same restrictions on the federal government.

Reconstruction-era interpretation and the Plessy decision

The Court that decided Plessy

During the Reconstruction era, the first truly landmark equal protection conclusion of the Supreme Court was Strauder v. West Virginia (1880). A black man convicted of murder by an all-white jury challenged a West Virginia statute excluding blacks from serving on juries. The Court asserted that the purpose of the Clause was

to assure to the colored race the enjoyment of all the civil rights that under the law are enjoyed by white persons, and to give to that race the protection of the full general government, in that enjoyment, whenever it should be denied past usa.

Exclusion of blacks from juries, the Court concluded, was a denial of equal protection to black defendants, since the jury had been "drawn from a panel from which the State has expressly excluded every homo of [the accused's] race."

The next important postwar example was the Civil Rights Cases (1883), in which the constitutionality of the Civil Rights Human action of 1875 was at issue. The Act provided that all persons should have "full and equal enjoyment of ... inns, public conveyances on country or water, theaters, and other places of public amusement." In its opinion, the Court promulgated what has since get known every bit the "State Action Doctrine," which limits the guarantees of the equal protection clause only to acts done or otherwise "sanctioned in some mode" past the land. Prohibiting blacks from attending plays or staying in inns was "simply a private wrong," provided, of course, that the state'due south law saw it as a wrong. Justice John Marshall Harlan dissented alone, maxim, "I cannot resist the conclusion that the substance and spirit of the recent amendments of the Constitution have been sacrificed past a subtle and ingenious verbal criticism."

Harlan went on to argue that because (one) "public conveyances on land and h2o" use the public highways, and (2) innkeepers appoint in what is "a quasi-public employment," and (3) "places of public entertainment" are licensed nether the laws of the states, excluding blacks from using these services was an act sanctioned by the state.

A few years later, Justice Stanley Matthews wrote the Court's stance in Yick Wo five. Hopkins (1886).[4] He argued: "These provisions are universal in their application, to all persons within the territorial jurisdiction, without regard to any differences of race, of color, or of nationality; and the equal protection of the laws is a pledge of the protection of equal laws." Thus, the Clause would not be express to discrimination against African Americans, nor would it be express to equal enforcement of existing laws.

In its most contentious post-war interpretation of the equal protection clause, Plessy five. Ferguson (1896), the Supreme Court upheld a Louisiana Jim Crow law that required the segregation of blacks and whites on railroads and mandated dissever railway cars for members of the two races.[5] The Court, speaking through Justice Henry B. Dark-brown, ruled that the equal protection clause had been intended to defend equality in ceremonious rights, not equality in social arrangements. All that was therefore required of the law was reasonableness, and Louisiana'southward railway law amply met that requirement, existence based on "the established usages, customs and traditions of the people."

Justice Harlan over again dissented. "Every i knows," he wrote,

that the statute in question had its origin in the purpose, non and then much to exclude white

persons from railroad cars occupied past blacks, every bit to exclude colored people from coaches occupied by or assigned to white persons.... [I]north view of the Constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this land no superior, ascendant, ruling grade of citizens. There is no caste here. Our Constitution is color-bullheaded, and neither knows nor tolerates classes amid citizens.

Such "arbitrary separation" by race, Harlan concluded, was "a badge of servitude wholly inconsistent with the civil freedom and the equality earlier the constabulary established by the Constitution."[6]

Since Brown v. Board of Education (1954), Justice Harlan's dissent in Plessy has been vindicated as a matter of legal doctrine, and the clause has been interpreted as imposing a general restraint on the government'due south power to discriminate against people based on their membership in sure classes, including those based on race and sex activity (see beneath).

It was besides in the post-Ceremonious-War era that the Supreme Court first decided that corporations were "persons" within the meaning of the equal protection clause.[seven] However, the legal concept of corporate personhood predates the Fourteenth Amendment. Chief Justice Marshall wrote: "The great object of an incorporation is to bestow the grapheme and properties of individuality on a commonage and changing torso of men."[viii] Nevertheless, the concept of corporate personhood remains controversial.[nine] In the tardily nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Clause was used to strike down numerous statutes applying to corporations. Since the New Deal, however, such invalidations take been rare.[x]

Between Plessy and Chocolate-brown

While the Plessy majority's interpretation of the clause stood until Brown, the holding of Brown was prefigured, to some extent, past several earlier cases.

The beginning of these was Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada (1938), in which a black student at Missouri's all-blackness higher sought admission to the law school at the all-white University of Missouri—every bit there was no police school at the all-blackness college. Admission was denied him, and the Supreme Court, applying the split up-but-equal principle of Plessy, held that a Country's offering a legal education to whites merely non to blacks violated the Equal Protection Clause.

Smith v. Allwright (1944) and Shelley v. Kraemer (1948), though not dealing with education, indicated the Court'southward increased willingness to detect racial discrimination illegal. Smith declared that the Democratic primary in Texas, in which voting was restricted to whites alone, was unconstitutional, partly on equal protection grounds. Shelley concerned a privately made contract that prohibited "people of the Negro or Mongolian race" from living on a detail piece of land. Seeming to go against the spirit, if not the exact letter, of The Civil Rights Cases, the Court constitute that, although a discriminatory individual contract could non violate the Equal Protection Clause, the courts' enforcement of such a contract could: after all, the Supreme Courtroom reasoned, courts were role of the state.

More than important, however, were the companion cases Sweatt v. Painter and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, both decided in 1950. In McLaurin, the University of Oklahoma had admitted McLaurin, an African-American, only had restricted his activities there; he had to sit apart from the rest of the students in the classrooms and library, and could swallow in the cafeteria only at a designated table. A unanimous Court, through Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson, said that Oklahoma had deprived McLaurin of the equal protection of the laws:

There is a vast deviation—a Constitutional difference—between restrictions imposed by the country which prohibit the intellectual commingling of students, and the refusal of individuals to commingle where the state presents no such bar.

In Sweatt, the Court considered the constitutionality of Texas'due south state arrangement of law schools, which educated blacks and whites at split up institutions. The Court (again through Principal Justice Vinson, and once again with no dissenters) invalidated the school arrangement—non because information technology separated students, but rather considering the separate facilities were non equal. They lacked "substantial equality in the educational opportunities" offered to their students.

All of these cases, including Brown, were litigated by the National Clan for the Advancement of Colored People. It was Charles Hamilton Houston, a Harvard Law School graduate and a law professor at Howard Academy, who in the 1930s first began to claiming racial discrimination in the federal courts. Thurgood Marshall, a quondam student of Houston'south and the future Solicitor General and Acquaintance Justice of the Supreme Court, joined him. Both men were extraordinarily skilled appellate advocates, but role of their shrewdness lay in their careful selection of which cases to litigate—of which situations would be the best legal proving grounds for their cause.[11]

Dark-brown and its consequences

When Earl Warren became Chief Justice in 1953, Chocolate-brown had already come earlier the Court. While Vinson was still Chief Justice, there had been a preliminary vote on the case at a conference of all 9 justices. At that time, the Courtroom had divide, with a bulk of the justices voting that school segregation did non violate the Equal Protection Clause. Warren, however, through persuasion and expert-natured cajoling—he had been an extremely successful Republican politician before joining the Court—was able to convince all 8 acquaintance justices to join his stance declaring school segregation unconstitutional.[12] In that opinion, Warren wrote:

To separate [children in grade and high schools] from others of similar historic period and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a fashion unlikely ever to exist undone.... We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of "split up only equal" has no identify. Carve up educational facilities are inherently unequal.

The Court so set the case for re-argument on the question of what the solution would be. In Brown Ii, decided the following year, it was concluded that since the problems identified in the previous opinion were local, the solutions needed to be local likewise. Thus the court devolved say-so to local school boards and to the trial courts that had originally heard the cases. (Chocolate-brown had actually been comprised of four unlike cases from four different states.) The trial courts and localities were told to desegregate with "all deliberate speed."

Partly because of that enigmatic phrase, only mostly because of self-alleged "massive resistance" in the South to the desegregation decision, integration did not begin in any significant way until the mid-1960s and then only to a pocket-size caste. In fact, much of the integration in the 1960s happened in response not to Chocolate-brown but to the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Supreme Court intervened in a handful of cases in the belatedly 1950s and early 1960s, but its next major desegregation decision was Green v. School Board of New Kent Canton (1968), in which Justice William J. Brennan, writing for a unanimous Court, rejected a "freedom-of-selection" school plan every bit inadequate. This was a meaning human action; freedom-of-choice plans had been very common responses to Brown. Nether these plans, parents could choose to send their children to either a formerly white or a formerly black school. Whites about never opted to nourish blackness-identified schools, however, and blacks, fearing of violence or harassment, rarely attended white-identified schools.

In response to Light-green, many Southern districts replaced liberty-of-choice with geographically-based schooling plans; merely because residential segregation was widespread, this had little effect, either. In 1971, the Court in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education approved busing as a remedy to segregation; three years afterward, though, in the instance of Milliken v. Bradley (1974), it set bated a lower court club that had required the busing of students between districts, instead of merely within a commune. Milliken basically ended the Supreme Courtroom's major involvement in school desegregation; yet, up through the 1990s many federal trial courts remained involved in schoolhouse desegregation cases, many of which had begun in the 1950s and 1960s.[2] American public schoolhouse systems, especially in large metropolitan areas, to a large extent are still de facto segregated. Whether due to Chocolate-brown, to Congressional action or to societal change, the per centum of blackness students attending schoolhouse districts a majority of whose students were black decreased somewhat until the early on 1980s, at which bespeak that percent began to increase. By the late 1990s, the percentage of black students in mostly minority school districts had returned to nearly what it was in the late 1960s.

There are, broadly speaking, two means to explain America's marked lack of success in school integration in the five decades since Brown. One style, sometimes voiced by political conservatives, argues that Brown's relative failure is due to the inherent limitations of law and the courts, which simply exercise not accept the institutional competence to supervise the desegregation of whole school districts. Moreover, the federal government's, and particularly the Supreme Court's, hubris really provoked the resistance of locals, since didactics in the United States is traditionally a thing for local control. Alternatively, liberals argue that the Court's decree in Brown II was insufficiently rigorous to force segregated localities into action, and that real success began only subsequently the other 2 branches of the federal government got involved—the Executive Branch (under Kennedy and Johnson) past encouraging the Department of Justice to pursue judicial remedies against resistant schoolhouse districts, and Congress by passing the Civil Rights Human activity of 1964 and the Civil Rights Act of 1968.[13] Liberals also bespeak out that Richard Nixon's "southern strategy" was premised on a tacit back up of segregation that connected when Nixon came to office, and then that after 1968 the Executive was no longer behind the Courtroom's ramble commitments.[xiv]

Carolene Products and the diverse levels of Equal Protection scrutiny

Justice Harlan Stone, author of Carolene Products

Despite the undoubted importance of Brownish, much of mod equal protection jurisprudence stems from the fourth footnote in Us v. Carolene Products Co. (1938), a Commerce Clause and substantive due procedure example. In 1937, the Courtroom (in what was called the "switch in fourth dimension that saved nine") had loosened its rules for deciding whether Congress could regulate certain commercial activities. In discussing the new presumption of constitutionality that the Court would apply to economic legislation, Justice Harlan Stone wrote:

[P]rejudice confronting discrete and insular minorities may be a special status, which tends seriously to curtail the operation of those political processes ordinarily to be relied upon to protect minorities, and which may call for a correspondingly more than searching judicial enquiry.[15]

Thus were born the "more searching" levels of scrutiny—"strict" and "intermediate"—with which the Court would examine legislation directed at racial minorities and women. Although the Court first articulated a "strict scrutiny" standard for laws based on race-based distinctions in Hirabayashi 5. U.s. (1943) and Korematsu v. United States (1944), the Court did non apply strict scrutiny, by that name, until the 1967 case of Loving v. Virginia, and that intermediate scrutiny did non control the approbation of a majority of the Court until the 1976 case of Craig v. Boren.

The Supreme Court has divers these levels of scrutiny in the following mode:

- Strict scrutiny (if the law categorizes on the basis of race or national origin): the constabulary is unconstitutional unless it is "narrowly tailored" to serve a "compelling" government interest. In add-on, in that location cannot be a "less restrictive" alternative available to achieve that compelling interest.

- Intermediate scrutiny (if the law categorizes on the basis of sexual practice): the law is unconstitutional unless it is "essentially related" to an "of import" government involvement. Annotation that in by decisions "sex" generally has meant gender.

- Rational-basis exam (if the police categorizes on some other footing): the police force is constitutional so long equally it is "reasonably related" to a "legitimate" authorities interest.

There is, arguably, a quaternary level of scrutiny for equal protection cases. In United States 5. Virginia Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg eschewed the language of intermediate scrutiny for sex activity-based discrimination and instead demanded that litigants articulate an "exceedingly persuasive" statement to justify gender discrimination. Whether this was just a restatement of the doctrine of intermediate scrutiny or whether it created a new level of scrutiny betwixt the intermediate and strict standards is unclear.

Discriminatory intent or disparate impact?

Afterward Brown, questions still remained about the scope of the equal protection clause–for instance, whether or not the Clause outlaws public policies that cause racial disparities. Information technology has been debated, for case, whether a public school exam that has non been established for racist reasons, but that more white students than black students pass, could exist seen to violate the Clause, or whether it requires there to be some intentional discrimination.

The Supreme Courtroom has answered that the equal protection clause itself does not foreclose policies which lead to racial disparities, simply that Congress may past legislation prohibit such policies.

Take, for case, Title Vii of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which forbids task discrimination on the basis of race, national origin, sex activity or religion. Title Vii applies both to private and to public employers. (While Congress applied Championship 7 to individual employers using its interstate commerce power, it applied Title VII to public employers under its power to enforce the Fourteenth Amendment. Title 7's standards for public and individual employers are the aforementioned.) The Supreme Court ruled in Griggs v. Duke Ability Co. (1971) that (i) if an employer'south policy has disparate racial consequences, and (ii) if the employer cannot give a reasonable justification for such a policy on grounds of "business necessity," and then the employer's policy violates Title VII. In the years since Griggs, courts have defined "business organization necessity" as requiring the employer to prove that whatever is causing the racial disparity—exist it a test, an educational requirement, or some other hiring practise—has a demonstrable factual human relationship to making the visitor more than assisting.[sixteen]

In situations involving but the equal protection clause, however, the focus of the court is on discriminatory intent. Such intent was manifested in the seminal case of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Corp. (1977). In that case, the plaintiff, a housing programmer, sued a city in the suburb of Chicago that had refused to re-zone a plot of land on which the plaintiff intended to build low-income, racially integrated housing. On the face, in that location was no clear bear witness of racially discriminatory intent on the part of Arlington Heights's planning commission. The result was racially disparate, notwithstanding, since the refusal supposedly prevented more often than not African-Americans and Hispanics from moving in. Justice Lewis Powell, writing for the Court, stated, "Proof of racially discriminatory intent or purpose is required to testify a violation of the Equal Protection Clause." Disparate affect merely has an evidentiary value; absent a "stark" pattern, "impact is not determinative." (See also Washington v. Davis (1976).)

Defenders of the rule in Arlington Heights and Washington v. Davis contend that the equal protection clause was non designed to guarantee equal outcomes, just rather equal opportunities and that therefore one should not be concerned with trying to set up every racially disparate effect. Ane should worry only about intentional discrimination. Others point out that the courts are merely enforcing the equal protection clause, and that if the legislature wants to right racially disparate effects, it may do and then through further legislation.[17] However, the Court has put significant limits on the congressional power of enforcement.[18]

Critics argue, on the other mitt, that the rule would exculpate many instances of racial discrimination, since it is possible for a discriminating party to hide its true intention. To uncover the motives of the parties, the court should likewise consider whether the measure at upshot would have disparate impact, critics argue.[19] This debate goes on almost entirely in the university, since the Supreme Courtroom has not inverse its basic arroyo as outlined in Arlington Heights.

Doubtable classes

The Supreme Court has seemed unwilling to extend "suspect course" condition (i.e., status that makes a law that categorizes on that basis suspect, and therefore deserving of greater judicial scrutiny) to groups other than women and racial minorities. In Urban center of Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Center, Inc. (1985), the Court refused to make the developmentally disabled a suspect form. Many commentators have noted, notwithstanding—and Justice Marshall then notes in his fractional concurrence—that the Court does appear to examine the City of Cleburne'due south denial of a allow to a group dwelling house for developmentally disabled people with a significantly higher degree of scrutiny than is typically associated with the rational-footing test.[xx]

In Lawrence v. Texas (2003), the Court struck downward a Texas statute prohibiting homosexual sodomy on substantive due process grounds. In Justice Sandra Day O'Connor's opinion concurring in the judgment, however, she argued that past prohibiting only homosexual sodomy, and not heterosexual sodomy as well, Texas's statute did not meet rational-basis review under the Equal Protection Clause; her opinion prominently cited City of Cleburne.

Notably, O'Connor did not claim to apply a higher level of scrutiny than mere rational basis, and the Court has not extended doubtable-class status to sexual orientation. Much as in City of Cleburne, though, the Courtroom's decision in Romer v. Evans (1996), on which O'Connor as well relied in her Lawrence opinion, and which struck down a Colorado constitutional subpoena aimed at denying homosexuals "minority status, quota preferences, protected condition or [a] claim of discrimination," seemed to employ a markedly higher level of scrutiny than the nominally applied rational-basis test.[21] While the courts accept applied rational-footing scrutiny to classifications based on sexual orientation, it has been argued that discrimination based on sex should be interpreted to include discrimination based on sexual orientation, in which example intermediate scrutiny could apply to gay rights cases.[22]

Affirmative activeness

Affirmative action is the policy of consciously setting racial, ethnic, religious, or other kinds of diversity as a goal inside an system, and, in lodge to see this goal, purposely selecting people from sure groups that have historically been oppressed or denied equal opportunities. In affirmative action, individuals of one or more than of these minority backgrounds are preferred—ceteris paribus—over those who do not have such characteristics; such a preferential scheme is sometimes effected through quotas, though this need not necessarily be and then.

Although there were forms of what is now called affirmative action during the Reconstruction (almost of which were implemented by the same persons who framed the Fourteenth Amendment.[23]) the mod history of affirmative action began with the Kennedy administration and started to flourish during the Johnson assistants, with the Civil Rights Human action of 1964 and ii Executive Orders. These policies directed agencies of the federal government to employ a proportionate number of minorities whenever possible.

Several important affirmative activity cases to reach the Supreme Court have concerned government contractors—for instance, Adarand Constructors five. Peña (1995) and City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co. (1989). Merely the most famous cases have dealt with affirmative action every bit practiced by public universities: Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978), and two companion cases decided past the Supreme Court in 2003, Grutter five. Bollinger and Gratz v. Bollinger.

In Bakke, the Court held that racial quotas are unconstitutional, but that educational institutions could legally use race equally i of many factors to consider in their admissions procedure. In Grutter and Gratz, the Court upheld both Bakke as a precedent and the admissions policy of the Academy of Michigan police force school. In dicta, withal, Justice O'Connor, writing for the Courtroom, said she expected that in 25 years, racial preferences would no longer be necessary. In Gratz, the Court invalidated Michigan's undergraduate admissions policy, on the grounds that unlike the law school's policy, which treated race non as one of many factors in an admissions process that looked to the individual bidder, the undergraduate policy used a point organization that was excessively mechanistic.

In these affirmative action cases, the Supreme Court has employed, or has said it employed, strict scrutiny, since the affirmative action policies challenged by the plaintiffs categorized by race. The policy in Grutter, and a Harvard College admissions policy praised by Justice Powell's opinion in Bakke, passed muster because the Court deemed that they were narrowly tailored to achieve a compelling interest in multifariousness. On one side, critics have argued that the scrutiny the Court has applied is much less searching than true strict scrutiny, and that the Courtroom has acted non as a principled legal establishment but every bit a biased political one.[24] On the other side, information technology is argued that the purpose of the Equal Protection Clause is to prevent the socio-political subordination of some groups by others, not to prevent classification; since this is so, non-invidious classifications, such as those used past affirmative action programs, should not be subjected to heightened scrutiny.[25] [26]

The Equal Protection Clause and voting

Although the Supreme Court had ruled in Nixon v. Herndon (1927) that the Fourteenth Amendment prohibited denial of the vote based on race, the beginning modernistic application of the Equal Protection Clause to voting law came in Bakery v. Carr (1962), where the Courtroom ruled that the districts that sent representatives to the Tennessee state legislature were and then malapportioned (with some legislators representing ten times the number of residents equally others) that they violated the Equal Protection Clause. This ruling was extended ii years later on in Reynolds 5. Sims (1964), in which a "ane human, one vote" standard was laid down; in both houses of country legislatures, each resident had to be given equal weight in representation.

Information technology may seem counter-intuitive that the equal protection clause should provide for equal voting rights; after all, it would seem to brand the Fifteenth Amendment and the Nineteenth Amendment redundant. Indeed, it was on this statement, as well as on the legislative history of the Fourteenth Amendment, that Justice John M. Harlan (the grandson of the earlier Justice Harlan) relied in his dissent from Reynolds. Harlan quoted the congressional debates of 1866 to show that the framers did not intend for the Equal Protection Clause to extend to voting rights, and in reference to the Fifteenth and Nineteenth Amendments, he said:

If ramble amendment was the only means by which all men and, later, women, could be guaranteed the right to vote at all, even for federal officers, how tin information technology be that the far less obvious right to a detail kind of apportionment of country legislatures ... can be conferred by judicial structure of the Fourteenth Amendment? [Emphasis in the original.]

However, Reynolds and Baker exercise not lack a rationale, if seen from another perspective. The Supreme Court has repeatedly stated that voting is a "fundamental right" on the same plane as spousal relationship (Loving five. Virginia), privacy (Griswold v. Connecticut (1965)), or interstate travel (Shapiro 5. Thompson (1969)). For any abridgment of those rights to be ramble, the Courtroom has held, the legislation must pass strict scrutiny.[27] Thus, on this business relationship, equal protection jurisprudence may be appropriately applied to voting rights.

A recent utilize of equal protection doctrine came in Bush 5. Gore (2000). At consequence was the controversial recount in Florida in the backwash of the 2000 presidential election. There, the Supreme Courtroom decided that the different standards of counting ballots beyond Florida violated the equal protection clause. Information technology was non this determination that proved specially controversial among commentators, and indeed, the proposition gained seven out of nine votes; Justices Souter and Breyer joined the bulk of five—merely only, it should be emphasized, for the finding that there was an Equal Protection violation. What was controversial was, offset, the remedy upon which the majority agreed—that even though there was an equal protection violation, in that location was non enough fourth dimension for a recount—and second, the proposition that the equal protection violation was true only on the facts of Bush v. Gore; commentators suggested that this meant that the Court did not wish its conclusion to take whatsoever precedential effect, and that this was evidence of its unprincipled controlling.[28] [29]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.i Eric Foner, America'southward Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877 (Perennial, 1989, ISBN 006091453X).

- ↑ 2.0 two.1 2.2 Paul Brest, Sanford Levinson, J.K. Balkin, and Akhil Reed Amar (eds.). Processes of Constitutional Decisionmaking: Cases and Materials (Aspen Constabulary & Business, 2000, ISBN 978-0735512504).

- ↑ Bruce A. Ackerman, We the People, Volume ii: Transformations (Belknap Press, 2000, ISBN 0674003977), 99–252.

- ↑ 118 U.S. 355 Yick Wo five. Hopkins (1886). Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ↑ C. Vann Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow (Oxford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0195146905), 6, 69–70.

- ↑ For a skeptical evaluation of Harlan, encounter Gabriel J. Mentum, "The Plessy Myth: Justice Harlan and the Chinese Cases," 82 Iowa L. Rev. 151 (1996).

- ↑ See Santa Clara Canton v. Southern Pacific Railroad, 118 U.S. 394 (1886). The Court alleged that it did not demand to hear argument on whether the Equal Protection Clause protected corporations, because "we are all of the opinion that it does." Id. at 396.

- ↑ Providence Bank v. Billings (1830). Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ↑ Carl J. Mayer, Personalizing the Impersonal: Corporations and the Nib of Rights Hastings Law Journal 41(3) (1990): 577. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ↑ David P. Currie, "The Constitution in the Supreme Court: The New Bargain, 1931–1940," 54 U. Chi. L. Rev. 504, 547 (1987).

- ↑ Aldon D. Morris, Origin of the Civil Rights Movements (Gratuitous Press, 1986, ISBN 0029221307).

- ↑ Richard Kluger, Simple Justice (Vintage, 1977, ISBN 0394722558).

- ↑ It is important to note that the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1968 were enacted under both the Commerce Clause and section v of the Fourteenth Amendment. Insofar as those Acts regulate "individual" deport under the rubric laid down by the Civil Rights Cases, the Acts were passed by Congress under its Commerce Clause powers. The Supreme Court unanimously deemed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 constitutional under the Commerce Clause in Katzenbach v. McClung, 379 U.S. 294 (1964) and Heart of Atlanta Motel five. United states, 379 U.S. 241 (1964). In Fitzpatrick five. Bitzer (1976), the Supreme Court held that Title 7 of the Ceremonious Rights Deed of 1964 validly applied to public employers.

- ↑ For the history of the political branches' date with the Supreme Court's commitment to desegregation (and vice versa), see Lucas A. Powe, Jr., The Warren Courtroom and American Politics (Belknap Press: 2001, ISBN 0674006836); Nick Kotz, Judgment Days: Lyndon Baines Johnson, Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Laws That Changed America (Houghton Mifflin: 2004, ISBN 0618088253). For more on the debate, see Gerald N. Rosenberg, The Hollow Hope: Can Courts Bring About Social Alter? (Academy of Chicago: 1993, ISBN 0226727033).

- ↑ 304 U.Southward. 144, 152 north.iv (1938). For a theory of judicial review based on Stone's footnote, see John Hart Ely, Republic and Distrust (Harvard University Press, 1981, ISBN 0674196376).

- ↑ Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 is practical to individual employers such as Griggs Power through Congress'southward Commerce Clause power, not through the Fourteenth Amendment. (This is, of course, consistent with the state action doctrine articulated in the Ceremonious Rights Cases.) However, Title VII also applies to public employers, and the Supreme Court has consistently applied the same disparate affect doctrine to both private and public employers. Compare GRIGGS v. Knuckles POWER CO.(1971) with DOTHARD v. RAWLINSON(1977), a Championship 7 suit against the Alabama prison arrangement. Retrieved November xi, 2020.

- ↑ For this point, meet Don Herzog, ramble rights: 2 Left2Right, March 22, 2005. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ↑ Come across City of Boerne v. Flores, Board of Trustees of the University of Alabama five. Garrett, and United States v. Morrison.

- ↑ Contrast the Court'southward opinions in Arlington Heights and Washington 5. Davis with, for example, Linda Hamilton Krieger, "The Content of Our Categories: A Cognitive Bias Approach to Discrimination and Equal Protection Opportunity," 47 Stan. L. Rev. 1161 (1995), and Charles R. Lawrence III, "Reckoning with Unconscious Racism," 39 Stan. L. Rev. 317 (1987).

- ↑ See Gayle Lynn Pettinga, Notation, "Rational Basis with Bite: Intermediate Scrutiny by Whatsoever Other Proper noun," 62 Ind. 50.J. 779 (1987); Neelum J. Wadhwani, Notation, "Rational Reviews, Irrational Results," 84 Tex. L. Rev. 801, 809-811 (2006).

- ↑ Joslin Courtney, "Equal Protection and Anti-Gay Legislation," 32 Harv. C.R.-C.L. Fifty. Rev. 225, 240 (1997) ("The Romer Court applied a more 'active,' Cleburne-like rational basis standard ..."); Robert C. Farrell, "Successful Rational Footing Claims in the Supreme Court from the 1971 Term Through Romer five. Evans," 32 Ind. L. Rev. 357 (1999).

- ↑ Andrew Koppelman, "Why Discrimination against Lesbians and Gay Men is Sexual activity Bigotry," 69 New York University Law Review 197 (1994).

- ↑ Eric Schnapper, Affirmative Action and the Legislative History of the Fourteenth Amendment Virginia Law Review 71(753) (1985). Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ↑ Peter H. Schuck, Reflections on Grutter Jurist, September 5, 2003. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ↑ Reva B. Siegel, Equality Talk: Antisubordination and Anticlassification Values in Ramble Struggles over Dark-brown Harvard Law Review 117(1470) (2003-2004). Retrieved November xi, 2020.

- ↑ Stephen L. Carter, When Victims Happen to Be Black The Yale Police force Periodical 97(three) (1988): 420-447. Retrieved November xi, 2020.

- ↑ The rights to privacy and to interstate travel are part of the Supreme Courtroom'southward substantive due process jurisprudence, and therefore are not derived from the equal protection clause; rather, the Court imported the standard of strict scrutiny from equal protection jurisprudence into substantive due process jurisprudence. This "importation" is farther complicated by the fact that some cases, such equally Loving v. Virginia, actually combine Equal Protection problems with substantive due procedure issues. The right to vote, nevertheless, seems to be an exception to the foregoing, in that the noun right to vote appears to derive not from the Due Process Clause but from the Equal Protection Clause. (Run across the dicta and concurring opinions in the landmark instance of San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez.)

- ↑ Bruce A. Ackerman (ed.), Bush v. Gore: The Question of Legitimacy (Yale Academy Press, 2002, ISBN 0300093799).

- ↑ Cass R. Sunstein and Richard A. Epstein (eds.), The Vote: Bush-league, Gore, and the Supreme Court (Academy of Chicago Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0226213071).

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ackerman, Bruce. We the People: Book 2: Transformations. Belknap Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0674003972

- Ackerman, Bruce (ed.). Bush v. Gore: The Question of Legitimacy. Yale Academy Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0300093797

- Brest, Paul, et al (eds.). Processes of Constitutional Decision making: Cases and Materials. Aspen Law & Business, 2000. ISBN 978-0735512504

- Ely, John Hart. Democracy and Distrust. Harvard, 1981. ISBN 0674196376.

- Foner, Eric. America'due south Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877. Harper Perennial, 1989. ISBN 006091453X

- Foner, Eric. Reconstruction. Harper Perennial, 1989. ISBN 978-0060914530

- Kluger, Richard. Simple Justice. Vintage, 1977. ISBN 978-0394722559

- Kotz, Nick. Judgment Days: Lyndon Baines Johnson, Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Laws That Changed America. Houghton Mifflin, 2004. ISBN 0618088253

- Morris, Aldon D. Origin of the Civil Rights Movements. Complimentary Press, 1986. ISBN 0029221307

- Powe Jr., Lucas A.; The Warren Court and American Politics. Belknap Press, 2002. ISBN 0674006836

- Rosenberg, Gerald N. The Hollow Promise: Can Courts Bring About Social Change?. Academy Of Chicago Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0226727035

- Sunstein, Cass R., and Richard A. Epstein (eds.). The Vote: Bush-league, Gore, and the Supreme Court. Academy of Chicago Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0226213071

- Woodward, C. Vann. The Strange Career of Jim Crow. Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0195146905

| United States Constitution | |

|---|---|

| Formation | History • Articles of Confederation • Annapolis Convention • Philadelphia Convention • New Jersey Plan • Virginia Plan • Connecticut Compromise • Signatories • Massachusetts Compromise • Federalist Papers |

| Amendments | Bill of Rights • Ratified • Proposed • Unsuccessful • Conventions to advise • State ratifying conventions |

| Clauses | Appointments • Instance or controversy • Citizenship • Commerce • Confrontation • Contract • Copyright • Due Process • Equal Protection • Establishment • Exceptions • Complimentary Exercise • Full Organized religion and Credit • Impeachment • Natural–born citizen • Necessary and Proper • No Religious Test • Presentment • Privileges and Immunities (Art. Iv) • Privileges or Immunities (14th Better.) • Spoken communication or Debate • Supremacy • Suspension • Takings Clause • Taxing and Spending • Territorial • War Powers |

| Interpretation | Theory • Congressional enforcement • Double jeopardy • Fallow commerce clause • Enumerated powers • Executive privilege • Incorporation of the Bill of Rights • Nondelegation • Preemption • Separation of church and state • Separation of powers |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New Earth Encyclopedia standards. This commodity abides by terms of the Creative Eatables CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click hither for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions past wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Equal_Protection_Clause history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

- History of "Equal Protection Clause"

Note: Some restrictions may apply to utilize of individual images which are separately licensed.

Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Equal_Protection_Clause

0 Response to "Neelum J Wadhwani Rational Review Irrational Results 84 Tex L Rev 801"

Post a Comment